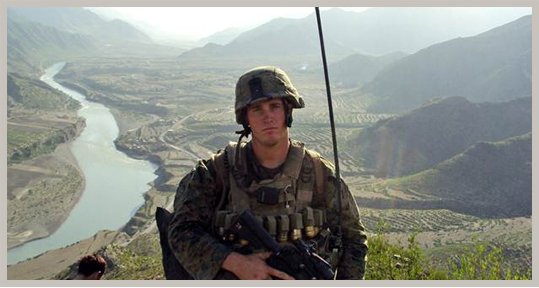

Medal of Honor to Marine Cpl. Dakota Meyer

Medal of Honor to Marine Cpl. Dakota Meyer

Marines who, one day in September 2009, were abandoned by their chain of command and relied on their own initiative to dislodge a fierce enemy. Their battle has entered military folklore and resulted not only in today’s Medal of Honor but in two Navy Crosses, two investigations for dereliction of duty, three letters of severe reprimand, and a recommendation for a second Medal of Honor.

The setting was the remote Afghan village of Ganjigal, on the Pakistan border, where elders had requested aid in repairing a mosque. Hoping to win hearts and minds, a U.S.-trained Afghan battalion agreed to help. At dawn, about 100 Afghan soldiers and a dozen U.S. Marine advisers entered the valley where Ganjigal is found, picking their way up a narrow, rocky wash toward the stone houses dug into the far end.

It was a setup. Hidden inside the houses and along the wash were 60 jihadists from Pakistan. The ambushers opened fire with machine guns, mortars and rockets. Immediately the foot patrol was pinned down and taking casualties.

Back at the valley’s entrance, 21-year-old Cpl. Meyer listened to radio calls for artillery fire that were refused by officers at higher headquarters due to concern for endangering villagers. Cpl. Meyer hopped into the gun turret of a Humvee and persuaded a fellow adviser, Sgt. Juan Rodriguez-Chavez, to drive him straight into the battle.

When the Humvee lurched into the wash, Cpl. Meyer saw the bodies of roughly a dozen Afghan soldiers strewn across the terrain, some dead and others crying. With bullets striking his truck, he leaped out, stuffed five wounded Afghans inside, and then hopped back up behind the machine gun and hammered away as the pulverized vehicle crawled out of the wash.

Leaving the wounded in the rear, Cpl. Meyer and Sgt. Rodriguez-Chavez swapped Humvees. This time the enemy was waiting in a dry streambed. Rocket-propelled grenades and machine-gun bullets followed Cpl. Meyer as he repeatedly left his armored turret to load the truck with wounded Afghan soldiers. At one point, he shot a tall man with a black beard. When another leapt forward under the barrel of his machine gun, Cpl. Meyer grabbed his M4 rifle and shot him in the head.”You’ll have to kill me,” he shouted in the rage of battle (he had expected to be killed, he told me a few days later at his outpost in Afghanistan), “because that’s the only way you’ll stop me.”

When Cpl. Meyer and Sgt. Rodriguez-Chavez again dropped off the wounded in the rear, they bumped into a backup American platoon in armored vehicles. The platoon refused to join them, so they went back in for a third time with no backup, driving into a torrent of automatic-weapons fire so a group of trapped American advisers could escape. Cpl. Meyer watched women and children darting among the houses, carrying ammunition to the jihadists.

Cpl. Meyer, a qualified sniper, was hit in the right elbow but continued to shoot left-handed until the feeling returned to his right hand. Over the radio, he listened to Capt. Will Swenson, an Army adviser who remained in the valley to fight, calling repeatedly for artillery fire, only to be rebuffed by headquarters.

Pulling back out, Cpl. Meyer took count. Four advisers were still missing. So he gathered those still willing to risk death. In addition to Sgt. Rodriguez-Chavez and Capt. Swenson, an Afghan interpreter and Lt. Ademola Fabayo, another adviser, climbed into the truck with Cpl. Meyer. An Army pilot in a tiny Kiowa helicopter, flying 10 feet above the ground, protected the Humvee from the rear. They drove back into the cauldron a fourth time. After seven hours of fighting, Cpl. Meyer found his four missing comrades, dead. At about the same time, the jihadists had collected their casualties and were trekking back into Pakistan.

Over the following months, two investigations resulted in three letters of reprimand for the unit commanders’ failure to provide fire support. Bitterness about the battle and its aftermath lingered among the families of the five dead Americans. While Lt. Fabayo and Sgt. Rodriguez-Chavez received the Navy Cross from the Marine Corps, Capt. Swenson quietly resigned from the Army with no recognition for his valor.

Cpl. Meyer protested against that oversight. Last month, Gen. John R. Allen, the new commander in Afghanistan, re-opened the record of that tumultuous day in Ganjigal. Given the four-star general’s personal interest, sworn statements attesting to Capt. Swenson’s valor were quickly found. Gen. Allen has since forwarded a Medal of Honor recommendation, saying it was the right thing to do despite a lapse of two years.

As for Dakota Meyer, his Medal of Honor citation speaks for itself. Ignoring withering fire, he had carried 12 wounded Afghans to safety and covered the withdrawal of 24 other Americans and Afghans. He had killed at least eight enemy fighters. He would not be refused in battle.

Men do not suddenly acquire unshakable determination to face almost certain death. At the age of four, young Dakota wanted to drive the old tractor on the family farm in Kentucky. His father told him he had to be old enough to turn the hand crank. An hour later, the tractor roared to life—Dakota had repeatedly jumped from the tractor hood onto the crank until it turned over. When he was five, he solemnly assured his grandmother that he would guard her against robbers. A rugged athlete in high school, he also tutored autistic students. He volunteered for Afghanistan as his second combat tour and risked death to rescue Afghans as well as Americans.

Cpl. Meyer set the example, but he could not have succeeded alone. Others of like mind joined him. Their shared tenacity wasn’t rooted solely in fighting for their fellow squad members. In fact, the core group at the end of the fight didn’t know each other that well. Capt. Swenson had only a passing acquaintance with Cpl. Meyer, while Lt. Fabayo and Sgt. Rodriquez-Chavez lived at a different base.